Recently, India became the 4th largest economy. As usual, X (formerly Twitter) erupted into a fierce debate. On one side were the people celebrating the achievement. While the other side was disparaging the achievement touting India’s low per-capita income1. Both are true. While raw size does confer power, the reality is that most Indians still don’t enjoy anywhere close to middle class living standards.

India has made great strides in reducing extreme poverty. That’s an applause worthy achievement. At the same time, there are other human development indices where the country is sorely lagging2. Necessities like education, electricity and water still haven’t reached the whole country. India’s per capita income is around $3,000. That puts it firmly in the lower middle income economies.

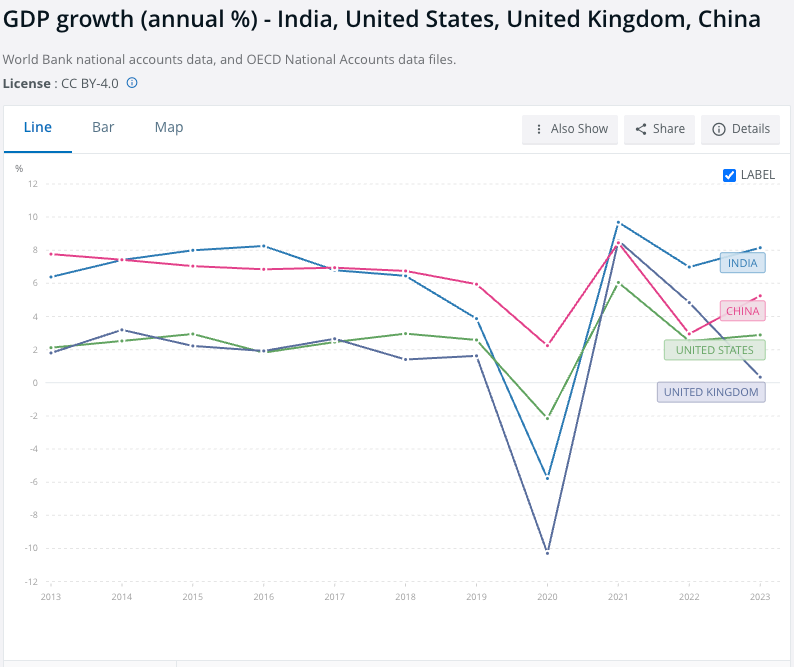

At present, the country is growing at around 6-7% per annum. While it is the fastest growing large economy, this growth is far too slow to deliver on the aspirations of hundreds of millions of Indians. If this rate of growth were to continue for another 20 years, India’s per capita income would only be around $10,000-$11,000. For reference, China today has a per capita income of $13,000. As can be seen from the graph below this paragraph, China is growing at a rate comparable to India even though its economy is multiple times larger.

From a macroeconomics perspective, there are a few things we would like to see in the Indian economy:

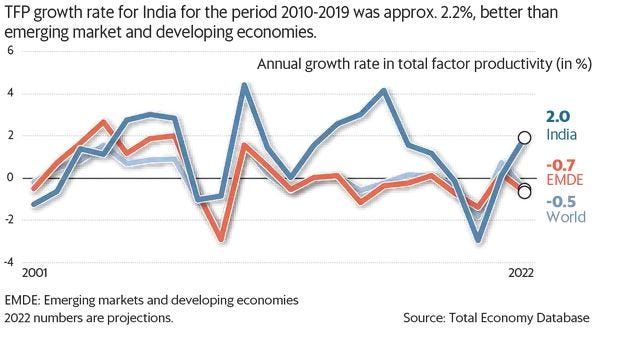

Growth in the productivity of Indian labor. Everyone is familiar with the idea that to produce more economic output, you need more labor and capital as input. However, that’s just using more resources as input to produce more output. The real trick to raising living standards is in producing more output using the same amount of inputs. This is called Total Factor Productivity (TFP).

It must generate millions of well paying jobs to absorb the mass of college graduates joining the labor force every year. Agriculture is a low productivity enterprise and the economy must also generate enough jobs to transition India’s labor from agriculture into higher paying manufacturing and services sectors.

The economy must transition to a market economy. India has immense distortions in its economy. From subsidized electricity for consumers to Minimum Support Prices (MSP) for farmers, the economy doesn’t allow market forces to guide towards an optimal outcome. I’m not an advocate for anarcho-capitalism, but socialist thought runs deep in Indian policy making circles.

All of this requires real growth in the double digits at the very least. How does India deliver on this? Where does future growth come from? Does this mean compromising with welfare nets? Before exploring these questions, let’s take a quick detour into what productivity actually means.

Total Factor Productivity

To understand the malaise plaguing much of the Indian economy requires understanding the concept of productivity. There’ll be some basics math, but I promise that you will come away with a much better understanding of macroeconomics if you stick with it.

In order to produce more output, you need more inputs. What are inputs? Depending on the model you use, there will be anywhere from 2-5 inputs. To simplify, we’ll only take the case when there are two inputs: Labor (L) and Capital (K)3. Some products require more of capital, while some might require more labor. Manufacturing semiconductors requires immense capital and comparatively less labor, whereas growing wheat requires lot of labor but relatively less capital. So how do we put it all together?

Y= K⍺Lβ

This is a standard production function that captures the fact that the output (Y) is dependent on the input of capital (K) and labor (L). The indices ⍺ and β are output elasticities. They indicate how much output changes, if the input changes by 1%. Essentially, let’s say we decide to buy one more tractor. How much more wheat could be harvested? Or if 10 more laborers were hired, how much more rice could be grown?

But there’s a crucial missing piece here. Two farmers with identical inputs—say, 10 tractors and 2 laborers—or two semiconductor firms equipped with the same 2 lithography machines and 50 engineers, might end up producing vastly different quantities of wheat or chips. Why? The answer lies in the efficacy with which those inputs are employed.

This efficacy is formally known as the Productivity constant (A) often called Total Factor Productivity (TFP). With that our equation becomes the Cobb-Douglas Production function.

Y= AK⍺Lβ

This equation is tells us something profound. That in order to have continuously evolving living standards, the amount of stuff an economy produces with the same amount of inputs needs to increase. Eventually, the economy will run out of labor and capital and if inputs are being used inefficiently, living standards will stagnate. The only way out is to produce more with the same inputs.

What does this look like in practice? Employees could be trained in basic ERP or CRM software that enables businesses to maintain more accurate account records. Companies might adopt elementary planning tools like Jira to ensure optimal utilization of employee time. A sari-weaving cooperative could harness WhatsApp groups to coordinate orders, manage inventory, and ensure the timely procurement of raw silk. Even something as simple as shifting from handwritten ledgers to digital spreadsheets can dramatically enhance operational efficiency. On a broader scale, government initiatives to simplify GST regulations and labor laws could liberate hundreds of man-hours, allowing businesses to redirect their efforts toward more productive and value-creating activities.

With productivity out of the way, let’s take a look at major components of India’s economy and how growth could be extracted.

Labor Laws

I’ve written extensively about labor laws previously. Even the new labor laws that the current dispensation is promulgating leaves much to be desired. You can read my previous critique.

Broadly, the new labor laws simply raise the threshold at which stricter labor regulations apply. The Indian state is stuck in a Communist mindset where it sees itself as paternalistic. It feels that its duty is to prevent businesses from exploiting workers. In the process, it ends up reducing the very TFP that the economy needs to achieve double digit growth.

A good example to explore this fallacy are job security and strong unionization laws. If a company has above 300 workers4, then laying off or retrenching workers in response to worsening economic conditions requires a number of government permissions. There are numerous unintended consequences of this:

Because operating a factory is expensive, layoffs need to be done fast. With the slow pace of the bureaucracy, getting permits to retrench the workforce in a timely manner requires paying bribes. This adds to the cost of doing business.

If a company is wrapping up operations and wants to shut down its factories, it still requires government permission to stop paying its workforce. In turn, it increases the exit barriers for the company. Inevitably, while starting a factory, this exit cost will also need to be factored in. As a result, many factories which might have started, wouldn’t start at all.

Counter-intuitively, because firing is so much more difficult, large companies might decide to hire very cautiously. The job market which might have expanded rapidly otherwise, grows sluggishly.

Unions are great at collective bargaining. Commonly, unions negotiate pay scales based on tenure rather than performance. This is a kick in the teeth to meritocracy and disincentivizes upskilling. Which leads to stagnating productivity. And as we saw earlier, the only way to better standards is through productivity.

Unions also tend to negotiate generous pay for their members. As a result companies have less money to invest in upgrading capital which might be needed for improving productivity. Only increased productivity would allow a worker to produce more, enabling him to capture more of the value that he/she adds. Which is what eventually leads to higher remuneration.

Companies get negative returns to scale because there is a compliance cliff at the 300 employee mark. As you would expect, the vast majority of Indian firms employ less than a 100 people5. With these miniscule sizes, there are no returns to scale, and no benefit to specialization.

That’s why most countries in Europe struggling with unemployment are the ones that have strict labor laws. France, Italy, Spain and Britain have maintained rigid regulations around hiring and firing and are struggling with high employment and inflation leading to stagflation or low growth.

In contrast, the US has lax labor laws and allows hiring and firing much more liberally. More companies are willing to take risks and hire people to work for them. If thing do go south, the only sunk costs are the ones you’ve already paid.

There’s concrete evidence for this. In a 2004 paper in the Quarterly Journal of Economics (QJE), Besley and Burgess study labor laws and manufacturing activity in the 1958-1992 time period. Their findings are worth pondering over.

They show that pro-worker regulations in the Industrial Disputes Act6 (IDA) caused lower investment, employment and productivity in manufacturing.

Pro-worker regulations are directly correlated with an increase in urban poverty. If West Bengal had not amended its IDA7 in 1980, there would have been 1.8 million less urban poor in 1990. The total urban population of the state in 1990 was 18 million.

United Andhra Pradesh was the most pro-employer state according to their measures. Between 1958 and 1992, it grew at 6% per year. Without its pro-employer reforms, it would’ve grown only 4.1% per year. It would’ve had about 1.7 million more urban poor in 1990. The state had 17 million urbanites in 1990.

Their conclusion is excoriating:

The results of the paper leave little doubt that regulation of labor disputes in India has had quantitatively significant effects. In India, the hand of government has been at least as important as the invisible hand in determining resource allocation. This has provoked heated debate about which aspects of this role have constituted a brake on development. It is apparent that much of the reasoning behind labor regulation was wrong-headed and led to outcomes that were antithetical to their original objectives.

Bankruptcy and Exit Barriers

Things don’t always go according to plan. Companies might setup plants to manufacture products and discover the demand isn’t really there. The market undergoes sudden shifts — like the one induced by COVID — and entrenched companies face unforeseen difficulties necessitating a shutdown.

Life happens and companies should be allowed to liquidate, pay off their debtors and use their newly freed resources to venture into something new. This is nothing to be afraid of and is simply creative destruction at play.

It is unacceptable to have companies waiting multiple years to exit a failing business or a loss-making production plant. Recall the Cobb-Douglas production function above. While a company is waiting to exit, it is still paying its employees and its capital in the form of machinery or land is idling. The output of all those inputs is effectively zero.

Nokia’s case is particularly instructive here. It setup a factory in Tamil Nadu in the Sriperumbudur SEZ and started production in 2006. At its peak the factory employed close to 20,000 employees and produced 15 million phones a month. In 2013, the employees went on a strike and stopped work demanding higher pay. This was the time when iPhones and Android phones were starting to dominate the entire market and Nokia was facing tough competition. As a result, it decided to sell itself to Microsoft for USD 7.2 billion in 2014. The plant in Tamil Nadu wasn’t a part of the deal primarily because of the legal challenges. To get itself out of this mess, Nokia decided to exit production. It was able to layoff contract workers, but permanent workers were protected by the IDA. Until the dispute between the workers and Nokia continued, it was required by law to continue paying them. Ultimately, Nokia was able to sell the factory off to Salcomp — a Chinese firm — in 2020. In the interim, from 2014 to 2020, it was required to pay workers8.

Similar to Nokia, GM and Ford were lacking profits and decided to exit their plants in India. Ford had a plant in Chennai and GM had a plant in Pune. The barrier in this case was employee severances again. Even after generous severance offers by both the companies, there were still some employees that hadn’t accepted the deal. Buyers were unwilling to take on the costs of the retrenched labor at the plants. Since the workforce there was unionised, buyers were also not keen on taking on such workers.

As a result of these delays, the ultimate loser was the Indian workforce. Tons of resources were tied up without any commensurate output. Companies would be wary of making investments again. The job market lost out on thousands of well-paying jobs (relative to the entire economy).

While the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC) has been introduced 4 years ago, it hit a snarl in the Supreme Court where it questioned the sale of Bhushan Power and Steel Limited (BPSL). Such gridlock reduces investors’ confidence in the economy and the justice system.

The easiest way to start with reducing exit barriers is to ease stringent labor laws.

The Judiciary

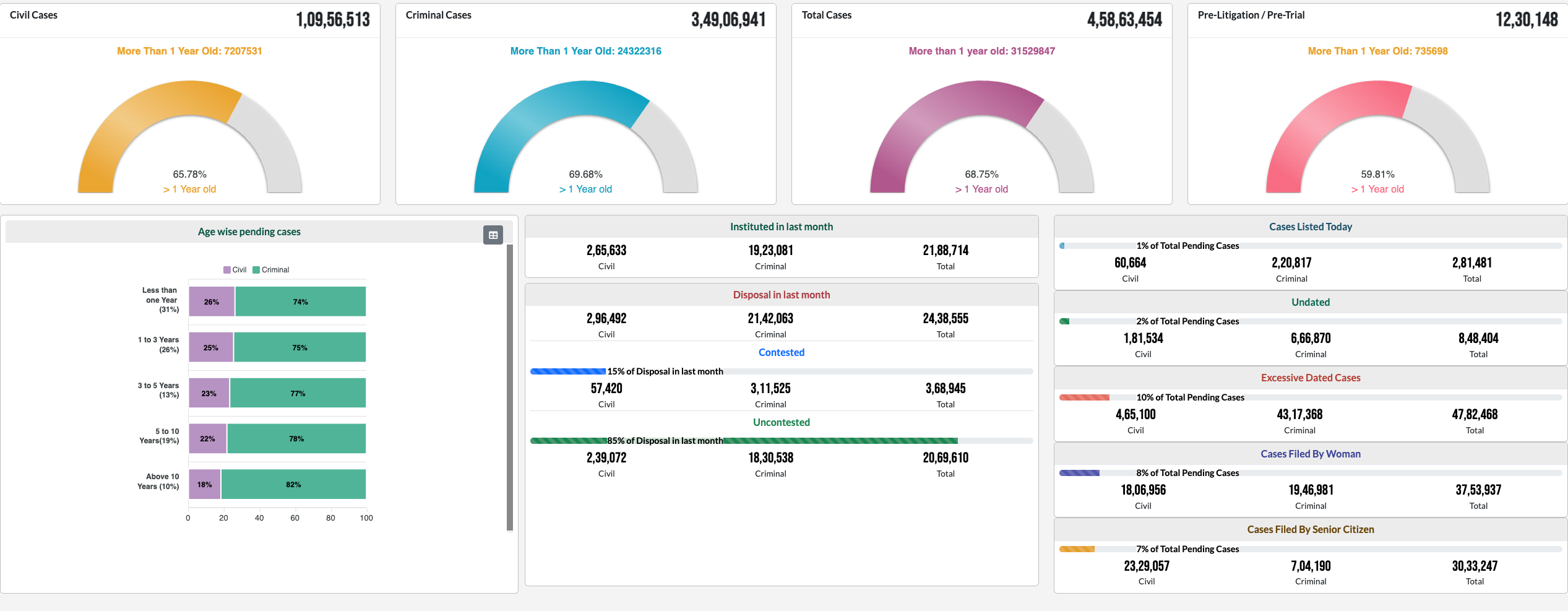

Consider these alarming facts about India’s justice system:

- There are 50 million cases pending in Indian courts. The Supreme Court itself has about 70,000 cases pending. At the current pace, without any new cases added, it would take 300 years for all cases to be resolved.

- Just last month, there were more than 2 million cases added to the backlog.

- There are 31 million cases that have been pending for more than a year.

- India has 15 judges per million people. The 1987 Law Commission recommends 50 judges per million people. The US has about 100 judges per million people.

Why does this matter in a conversation about the economy? Without a functional legal system, companies don’t have much faith in the sanctity of contracts. Would you entrust non-family members with high positions in your business if they could fleece and enforcing the law took the better part of a decade?

Nicholas Decker has an excellent post on the Indian justice system. While the entire post is worth reading, one part particularly caught my eye:

A study found that a firm receiving the management training increased their annual profits by 17%, or almost $300,000 a year. Since these are extremely simple interventions — things such as “write down what types of yarn you have and how much” and “have a schedule for repairing machines”, one wonders why the companies never adopted them on their own.

The commonly cited reason by firm owners and plant managers was that they simply didn’t know that that was what one should do. But not knowing is arguably downstream of firm owners being unable to delegate. Basically all decision making is done by the owners, and middle managers are not free to, nor are they incentivized to, introduce improvements of their own. The root of this is the fear of expropriation by the managers, for which the owners would have no timely recourse. If the courts were efficient enough to be a check on fraud, owners could trust their managers and implement better practices. Instead we are stuck in a world which no one wants.

[…]

What Boehm and Oberfield use is the age of a court, which strongly predicts how congested it is. If a new High Court is formed, it naturally starts out with no cases, and only accumulates them over time. Places with worse courts will do more things in house, and will not rely upon other companies to make products. This is a big deal! Being able to fragment your production allows for greater specialization by each of the parts. They estimate that simply making every court system like the least congested systems would, by itself, raise productivity by 4%.

Once again we circle back to productivity. Most of the productivity gains are lost due to the lumbering judiciary and we’re left with a tepid 7% growth rate. The study he cities claims that just making courts less congested increases the productivity by 4%. Plugging this into the Cobb-Douglas production function above, assuming that the inputs — capital and labor — remain constant, the economy could grow an additional 4% every year. This is such a low hanging fruit for achieving double digit growth.

The new GDP figures were released by the Ministry of Statistics and Planning Implementation (MoSPI). The upside in growth was a pleasant surprise9. However, private CapEx remains underwhelming. I’m willing to bet a large part of it is our clogged courts.

While the judiciary does need tough reforms, there is one low hanging fruit to be picked: Fill in vacant positions for judges. As of 15th April, 2024 there were 368 vacancies out of a total sanctioned strength of 1104 in High Courts across the country. In District and other Subordinate courts, there were about 5,000 vacancies against a total sanctioned strength of 23,000. These are significant vacancy ratios.

Electricity Distribution Boards, Agriculture and Welfare Spending

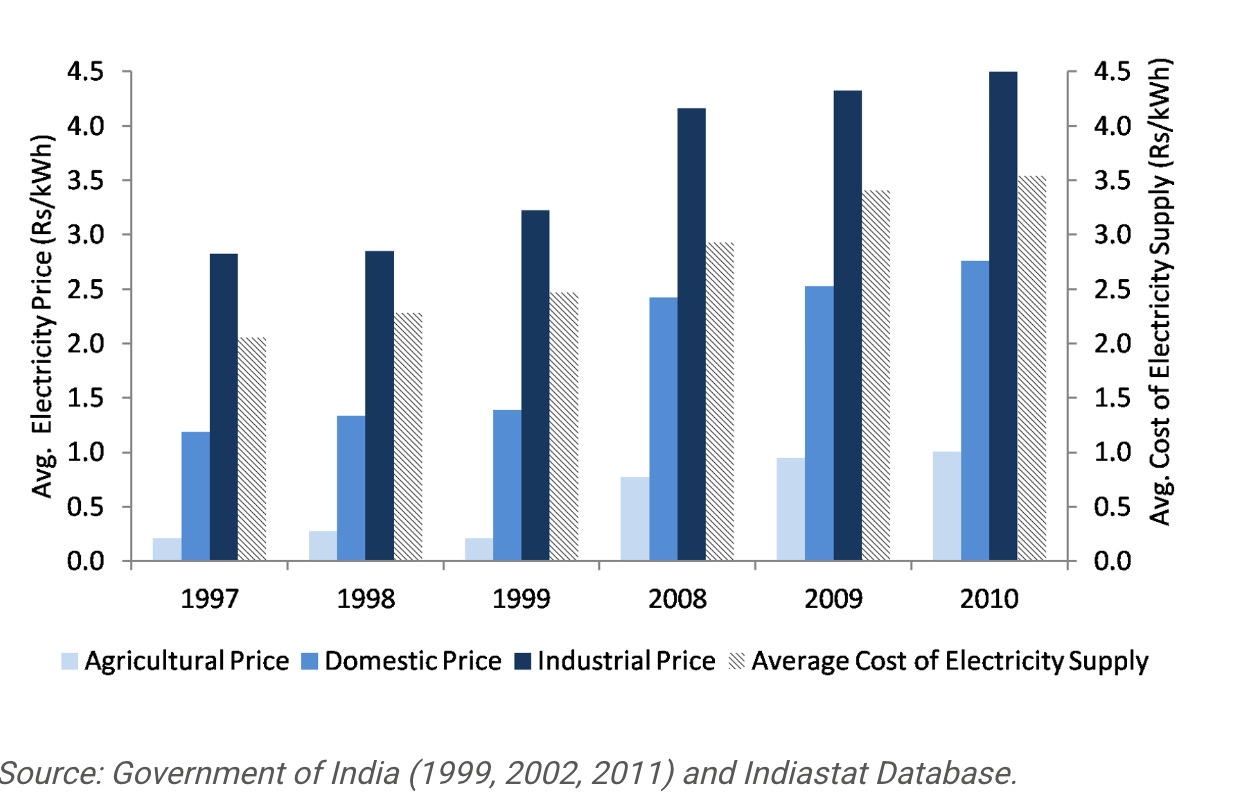

Electricity is a major input across all industries. Cheaper electricity does wonders to reduce the price of the final product. Subsidizing electricity for certain sectors encourages inefficient use and introduces distortions in the economy.

If it still isn’t clear who I’m pointing fingers at here, it is farmers. Consider the following sequence of events.

- Most states provide farmers with electricity at heavily subsidised rates.

- The central government offers a Minimum Support Price (MSP) for 26 crops, many of which are water intensive.

- Farmers are naturally incentivised to prioritise the MSP crops for guaranteed income.

- As a result of water intensive farming, the groundwater table sinks further down requiring more electricity to extract the groundwater.

- Expectedly, most electricity distribution boards (DISCOMS) are running in massive losses.

- Raising consumer electricity prices isn’t an option because the politician that allows it to happen will be losing the next election.

- The only recourse is to charge industry users higher rates to ensure power generation and distribution is still viable.

The consequences of such policies are disastrous across the board. Often, grasping the magnitude of ruination caused by policies is difficult because there’s no alternate world that we can observe where these policies haven’t been implemented. In their famous study, Hsieh and Klenow show that rectifying this misallocation could improve productivity anywhere from 40-60%. Everything else remaining constant, the Cobb-Douglas production function tells us that growth would also increase by 40-60% — which means this year’s GDP growth rate could have been as high as 10.5%.10

The above graph shows how much electricity costs to supply and what differenet classes of users pay for it. Agricultural users are heavily subsidized leaving domestic and industrial users to fill in the gaps. Abeberese (2017) shows that high electricity prices suppress industrial output. Using firm-level data, she shows that just a 1.4% reduction in electricity prices for industry, would result in a 2.8% increase in output. The increase in output would easily cover the reduction in subsidies making it a worthy trade-off.

If India intends to be a developed economy by 2047, it needs a per-capita income of at least USD 15,000. That’s 5 times the size of the current economy. A quick back-of-the-napkin calculation tells us that the average growth rate required is at least 10%11 sustained over 20 years. There would be bad years so the good years would need growth in the double digits sometimes to get there in time.

The only way to get there is to improve the productivity of the Indian economy across the board. It doesn’t have to involve large scale reforms that are politically unpalatable and risk losing elections. There are enough low hanging fruits to be picked.

Filling up judicial vacancies, phasing out subsidies and focusing on state capacity are just some of them. Ultimately, the goal is to improve productivity. The moment th economy starts to gain TFP, is when Indian growth really zooms up and goes parabolic.

Notes:

1. There’s a small, yet significant difference between per-capita income and per-capita GDP.

2. While these indices have their own measurement problems, the core issue of poor infrastructure, bad health and inadequate living standards remains.

3. The standard Cobb-Douglas production function uses labor and capital as inputs. The KLEMS model uses Capital (K), Labor (L), Energy (E), Materials (M) and Services (S).

4. This number is 100 in many states although the new labor codes do intend to raise the number to 300 everywhere in the state.

5. Until recently, stringent labor laws kicked in when firms employed about a 100 workers so there were tons of firms with 99 workers only. Talk about unintended consequences!

6. The IDA was the main law governing labor regulations until the new labor codes took over.

7. Which they can because labor laws fall under the Concurrent list of subjects.

8. From “No Country for Dying Firms: Evidence From India”

9. Although India really does need to get a handle on its statistics and data programme. There are serious issues with India’s statistics, primarily with the way GDP is computed. Read Carnegie Endowment’s report on the same for more details.

10. Assuming a 50% increase in growth over 7% is 10.5%.

11. We want to hit USD 15,000 in real dollar and not nominal dollar which are less valuable because of inflation.

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!